Supplemental Episode 005: Legendary Advisers

A little Christmas morning stocking stuffer: A look at some of the guys that Zhuge Liang keeps getting compared to.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: More Options

Transcript

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is a supplemental episode.

In this episode, I want to introduce you to a few of the legendary advisers in Chinese history. I’m going to cover four guys: Jiang (1) Ziya (3,2), Zhang (1) Liang (2), Guan (3) Zhong (4), and Yue (4) Yi (4). Ever since we were introduced to Zhuge Liang in the novel, we have been hearing a lot of comparisons to these guys, so I think it would be helpful to give you some context about who they were.

First, let’s talk about Jiang Ziya, the earliest of the four. He lived at the end of the Shang Dynasty, around the 1100s B.C. The Shang was considered the second Chinese dynasty, although it is the first dynasty for which we have solid evidence of its existence. The Shang was said to have lasted something like 700 years, but by the time of JIang Ziya, it was fading fast. According to some versions of his story, Jiang Ziya supposedly served in the court of the last king of the Shang for a while, but left because of the king’s wicked ways. From there, he was said to have traveled near and far to the surrounding kingdoms, but none of their rulers really made much use of him. Before you know it, Jiang Ziya was an old man who had accomplished little and was living in poverty.

First, let’s talk about Jiang Ziya, the earliest of the four. He lived at the end of the Shang Dynasty, around the 1100s B.C. The Shang was considered the second Chinese dynasty, although it is the first dynasty for which we have solid evidence of its existence. The Shang was said to have lasted something like 700 years, but by the time of JIang Ziya, it was fading fast. According to some versions of his story, Jiang Ziya supposedly served in the court of the last king of the Shang for a while, but left because of the king’s wicked ways. From there, he was said to have traveled near and far to the surrounding kingdoms, but none of their rulers really made much use of him. Before you know it, Jiang Ziya was an old man who had accomplished little and was living in poverty.

Meanwhile, one of the vassals of the Shang, King Wen (2) of the kingdom of Zhou, was in the midst of searching for talented men. As the story goes, one day, before the king went out hunting, he took the auspices, and the diviner informed him that on the north bank of the Wei (4) River, he would net a big catch, but that this catch would not be in the form of a dragon, a tiger, or a bear. Instead, he was told, he would find an official who would help him achieve his grand plans.

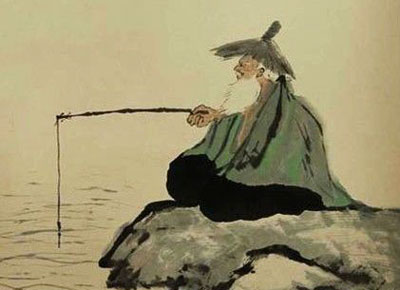

So King Wen (2) went off on his hunt, and on the north bank of the Wei (4) River, he came upon an old man sitting on a grass mat and fishing. King Wen noticed something odd about the old man’s fishing line. At the end of the line was not a hook, but a straight needle, or according to some version of the story, nothing at all. This obviously was not going to snag any fish.

Intrigued, the king asked the old man about his strange method of fishing. This old man, who of course, was none other than JIang Ziya, replied, “Those who are ready will come to me on their own volition.” He then added, “The willing will come; the unwilling will go away.”

When the king heard this, he couldn’t quite shake the feeling that the old man was maybe not talking so much about fish as he was about the king. So he began to converse with Jiang Ziya and soon recognized that he was talking to a man possessing great political and military knowledge. So the king asked Jiang Ziya to be his teacher. To show his respect, the king asked Jiang Ziya to sit in his chariot, then personally drove the chariot back to his capital, where he made Jiang Ziya his prime minister.

King Wen’s faith in Jiang Ziya was not misplaced. After King Wen died, his son, King Wu (3), came the throne and decided to overthrow the Shang Dynasty. Jiang Ziya was his main strategist in the ensuing war and was instrumental in the eventual victory that marked the beginning of the Zhou Dynasty, which would last about 800 years. For his contributions, Jiang Ziya was made the ruler of the vassal kingdom of Qi (2), and he ruled that territory wisely and made it prosper.

To this day, Jiang Ziya is something of a revered, half-mythical figure in China, and the benchmark against which all advisers who came afterward would be measured. And his rags-to-riches transformation in his old age gives us all hope that it’s never too late to make something of ourselves.

The next great adviser in our lineup is Guan (3) Zhong (4), who lived from 723 to 645 BC, during the Spring and Autumn period. During this period, even though the Zhou Dynasty still technically existed and the King of Zhou was technically the ruler of the empire, in reality he had little sway and all the vassal kingdoms were vying with each other for dominance. The aim of these individual kingdoms wasn’t so much to conquer the rest of the empire as it was to dominate the other kingdoms and make yourself the biggest, baddest kid on the block.

The next great adviser in our lineup is Guan (3) Zhong (4), who lived from 723 to 645 BC, during the Spring and Autumn period. During this period, even though the Zhou Dynasty still technically existed and the King of Zhou was technically the ruler of the empire, in reality he had little sway and all the vassal kingdoms were vying with each other for dominance. The aim of these individual kingdoms wasn’t so much to conquer the rest of the empire as it was to dominate the other kingdoms and make yourself the biggest, baddest kid on the block.

Guan Zhong’s father was an official in the state of Qi (2), which coincidentally, was the fiefdom that was ruled by Jiang Ziya some 400 years earlier. After his father died, Guan Zhong’s family fell into poverty. He tried his hand at business with a friend named Bao (1) Shuya (1,2). That venture went bust, though during his time as a two-bit merchant, Guan Zhong traveled all around, which gave him a lot of life experience. He also tried his hand at being a soldier, but fled in the face of battle. He later tried to become an official but also had no luck.

Eventually, though, Guan Zhong’s fortunes took a turn for the better. He and Bao (1) Shuya (1,2), who was a pretty learned scholar in his own right, became tutors to two of the sons of the Duke of Qi. This Duke had three sons. The eldest was his successor, but this heir was a man of dubious character. Guan Zhong and Bao Shuya, meanwhile, were tutors to the two younger sons, each taking on one prince.

After the old Duke died, his no-good heir came to the throne, and things soon hit the fan. The new Duke’s cousin, who held a grudge because of some personal slight, staged a coup, killed the Duke, and put himself on the throne. Amid the chaos, the dead Duke’s younger brothers, the ones tutored by Guan Zhong and Bao Shuya, fled with their teachers to different corners of the empire.

A year after the coup, the new new Duke got his comeuppance, as members of the ruling house staged their own coup and killed him. At this point, the state of Qi was without a ruler. This was the opportunity the two princes in exile were waiting for, and they both began to rush back, since the first one to make it home would have an advantage in vying for the throne.

Xiaobai (3,2), the prince who was tutored by Bao Shuya, set off first and looked to be the frontrunner. But Guan Zhong got wind of this, so he led some war chariots and raced on ahead of his own prince to cut off Xiaobai along the way. When he approached Xiaobai’s chariot, Guan Zhong suddenly shot an arrow at the prince. Prince Xiaobai was struck, spat up blood, and slumped in his chariot. Seeing that his master’s rival was now dead, Guan Zhong rode away, rejoined his prince, and continued on their journey at a leisurely pace.

Unbeknownst to Guan Zhong, however, Prince Xiaobai was very much alive. The arrow had struck his belt buckle, and Xiaobai, thinking quickly, bit his own tongue to spit up blood and make Guan Zhong think he was dead. But as soon as Guan Zhong was out of sight, Xiaobai and Bao Shuya pressed forward at double time, and they beat their rival home. Upon entering the capital, Xiaobai was crowned Duke Huan (2) of Qi.

This turn of events did not bode well for his brother. Guan Zhong and his prince soon discovered that they had been duped and that they were now out in the cold as far as the throne was concerned. At this time, they were backed by the state of Lu (3), and the Duke of Lu (3) launched an attack on Qi to try to put his man on the throne by force. But Duke Huan (2) of Qi repelled this attack and even chased the defeated Lu (3) troops back into their own territory. At this point, Duke Huan (2) wrote to the Duke of Lu (3) and told him that if he did not want any trouble, he needed to kill the renegade prince and hand over Guan Zhong. So Guan Zhong’s master was eventually forced to commit suicide, while Guan Zhong was placed in a prison cart and shipped back to Qi.

While this was going on, Duke Huan was getting his court in order, and he asked his teacher, Bao Shuya, to serve as his prime minister. Bao Shuya, however, told his pupil that he was not worthy and suggested another man for the job. And that man was … Guan Zhong.

Duke Huan was taken aback by this suggestion. I mean, did you forget that Guan Zhong was the guy who, you know, tried to put an arrow through my heart? But Bao Shuya told him that Guan Zhong was a rare talent, superior to me in every way. Besides, Bao Shuya said, Guan Zhong was merely serving his own master when he shot you, and you can’t fault a man for being loyal to his liege. Bao Shuya eventually convinced Duke Huan to drop his grudge.

When Guan Zhong’s prison cart arrived in Qi, Bao Shuya was at the border to greet him. Guan Zhong was released, given a bath and a fresh set of clothes, and told that, oh hey, instead of killing you, the Duke wants you to be his right-hand man. Guan Zhong was initially reluctant because 1) he failed to help his own master take the throne, and 2) he failed to follow his master in death. So what would people say if he now served his former enemy? But Bao Shuya eventually persuaded him to reconsider.

So now that both parties were receptive to each other, Duke Huan personally went to welcome Guan Zhong and entrusted him with the affairs of his kingdom. Guan Zhong lived up to Bao Shuya’s praise, as his policies made the kingdom of Qi strong and prosperous. Over the course of two decades, Guan Zhong helped Duke Huan defeat a bunch of rival kingdoms, until he was declared the hegemon, or in other words, the biggest, baddest kid on the block.

I’m leaving out a lot of details from Guan Zhong’s story, but I have two more legendary advisers to get to, so let’s keep moving. The next guy I want to cover is Yue (4) Yi (4), We don’t know the exact years of his life, but he lived during the Warring States period sometime in the 200s B.C. This period was more or less a continuation of the Spring and Autumn period of division. Yue Yi lived in the kingdom of Zhao (4) and began his career as an official there. But after the once powerful king of Zhao was starved to death in his own palace in a coup, Yue Yi left and went to the neighboring kingdom of Wei (4).

I’m leaving out a lot of details from Guan Zhong’s story, but I have two more legendary advisers to get to, so let’s keep moving. The next guy I want to cover is Yue (4) Yi (4), We don’t know the exact years of his life, but he lived during the Warring States period sometime in the 200s B.C. This period was more or less a continuation of the Spring and Autumn period of division. Yue Yi lived in the kingdom of Zhao (4) and began his career as an official there. But after the once powerful king of Zhao was starved to death in his own palace in a coup, Yue Yi left and went to the neighboring kingdom of Wei (4).

During this time, the small and weak kingdom of Yan (4) was being bullied by the powerful kingdom of Qi (2), to the point where the king of Yan (4) had to subjugate himself to Qi. But this king had grand ambitions and was courting men of talent. At that time, Yue Yi was sent by Wei as an envoy to the King of Yan (4). The King of Yan treated him as an honored guest and Yue Yi was convinced to remain in Yan and serve the king.

Meanwhile, the kingdom of Qi (2) kept getting stronger, to the point where its territory stretched for hundreds of miles (which was pretty big for the time), and for a while there, the king of Qi (2) actually called himself the emperor of the east. But this king was also arrogant and cruel toward his subjects, and in 284 B.C., the King of Yan (4) decided that the time had come to throw off his yoke and launch an attack on Qi.

At Yue Yi’s suggestion, Yan struck up an alliance with four other kingdoms. Yue Yi personally went to those kingdoms to secure the alliance, and then he commanded the combined armies of the five ally kingdoms.

Over the course of five years of warfare, Yue Yi and the ally forces defeated the army of Qi time and again and seized 70-some cities from Qi. It got to the point where Qi had only two cities left in its control. So the kingdom of Yan was riding high and enjoying prosperity and power like never before.

But Yue Yi was also smart enough to recognize that simply conquering cities by force was not a way to secure your hold on the newly won territories. If you don’t win the support of the local people, even if you conquered the entire kingdom of Qi, you would not be able to hold it. So instead of laying siege to the last two cities of Qi, he simply had his army surround them. Meanwhile, in the conquered territories, he made sure to respect and preserve the local customs and culture, and employed people who were well-known in those areas so as to earn the support of the locals.

But this plan would also turn out to be his undoing. In 279 BC, the King of Yan died, and his son came to the throne. Now this new king had had his differences with Yue Yi before he became king, and now he was persuaded by one of his advisers that Yue Yi was dragging his foot on taking the last two cities of Qi because he was trying to set himself up as the king of Qi. Growing suspicious, the new king of Yan decided to recall Yue Yi and put someone else in charge of the war. Yue Yi, recognizing which way the wind was blowing, feared for his life if he actually returned. So instead of going back to Yan, he fled to Zhao (4), one of the kingdoms in the alliance. Zhao (4) took him in and treated him extremely well so as to use his presence to keep the kingdoms of Yan and Qi on guard.

Yan’s war against Qi unraveled quickly after Yue Yi’s departure. Qi took advantage of his absence to launch a counterattack that drove the Yan army back until Qi had recovered all the cities it had lost. So all of Yan’s labor of the previous five years were for naught.

This setback made the new king of Yan regret his decision to replace Yue Yi, but at the same time, he was mad at Yue Yi for defecting to Zhao (4). So he sent a message to Yue Yi, in which the king simultaneously apologized for recalling him and admonished him for not coming home. Yue Yi responded with a famous letter in which he expressed his unwavering loyalty to the old king, and listed all of his grievances against the new king. The letter said that “Those who do good might not always be repaid in kind, and good beginnings do not ensure good endings.” This, he concluded, was reason enough to not serve a bad master and die an unjust death.

Brought to his senses by this letter, the king of Yan made Yue Yi’s son a high official in his court. Yue Yi, meanwhile, served as a diplomat between the kingdoms of Zhao and Yan and forged a strong connection between the two. However, he never would go home to Yan, dying in Zhao instead.

Alright, so that’s three down, and we have come to our final legendary adviser, Zhang Liang. He lived from 250 to 186 BC, and he was one of the top advisers for the Supreme Ancestor, the founding emperor of the Han (4) Dynasty.

Zhang Liang’s forefathers were high officials in one of the kingdoms of the latter stages of the Warring States period. But that kingdom, like everybody else, was vanquished by the kingdom of Qin (2), which united China under its first emperor and everyone’s favorite tyrant, Qin Shi (3) Huang (2). Deprived of a chance to follow in his forefathers’ footsteps and serve as an official for his home kingdom, Zhang Liang was hell bent on seeking revenge, so he devised a plot to assassinate Qin Shi Huang.

This assassination plan sounds a little kooky. Zhang Liang exhausted what money his family had to hire a strongman and made for him a hammer that weighed something like 130 pounds. Zhang Liang then managed to track down intel of the emperor’s whereabouts. At that time, Qin Shi Huang was making an inspection tour of the east. According to customs, the emperor’s chariot was pulled by six horses, while his officials’ chariots were pulled by four horses. So Zhang Liang’s plan was to have his strongman assassin lie in wait and then attack the guy in the six-horse chariot when the imperial procession passed.

So in the year 218 BC, this assassination attempt went down. As the emperor’s entourage passed, the assassin and Zhang Liang watched. There was just one problem: All the chariots were pulled by four horses. So Zhang Liang just instructed the assassin to attack the most-impressive looking chariot. The assassin sprang out and, wielding Thor’s hammer, clubbed to death the guy riding in that chariot. The assassin was immediately killed by the guards, but Zhang Liang slipped away in the chaos.

Later, however, Zhang Liang found out that, oops, he had killed the wrong guy. Qin Shi Huang, being the cruel egomaniac that he was, had made many enemies and had been on the receiving end of numerous assassination attempts. So by the time it was Zhang Liang’s turn to take a shot at the emperor, Qin Shi Huag was well-prepared. He had put four horses on all the chariots in his entourage and constantly changed which one he rode in. Thus thwarted but never identified, Zhang Liang took an alias and disappeared into obscurity.

That was not the end of Zhang Liang’s story, but rather the beginning. One day, as he was crossing a bridge, an old man walked past him. As he passed, the old man intentionally dropped one of his shoes off the bridge. He then turned and said to Zhang Liang, in a rather patronizing tone, “Son, go fetch that me, would ya?”

Zhang Liang was taken aback a bit by this, but he suppressed his displeasure and dutifully retrieved the shoe. The old man then raised his foot and told Zhang Liang to put the shoe back on. Zhang Liang felt like punching this guy for his disrespectful manners, but he had lived through so many hardships at that point that he had been humbled enough to tolerate this insult. So he kneeled and carefully put the shoe on the old man’s foot. Then, without a word of thanks, the old man laughed and walked away, leaving Zhang Liang on the bridge, probably thinking, “What the heck just happened?”

But momentarily, the old man came back on the bridge and told Zhang Liang, “You are worthy of being my pupil.” He then told Zhang Liang to meet him at the bridge at dawn in five days. He did not explain further, but Zhang Liang, despite having no idea what this was all about, nonetheless kneeled and thanked him respectfully.

So five days passed, and Zhang Liang rushed to the bridge at dawn. But lo and behold, the old man had arrived early and was waiting for him. When he saw Zhang Liang, the old man admonished him, “How can you be late to a meeting with an elder? Come back again in five days.” And then the old guy left.

Five days later, Zhang Liang returned, but the old man had pulled same stunt on him yet again. So Zhang Liang was told to come back in another five days. Now, a lot of people probably would’ve just said the heck with this, but Zhang Liang did not. Instead, five days later, he went to the bridge at MIDNIGHT and waited until dawn. This time, at last, his commitment and forbearance impressed the old man, who handed him a book and told him, “Ten years from now, the empire will be in chaos. Use this book to help build a new kingdom.” And then he left.

Zhang Liang took a look and saw that he had been given a copy of The Six Secret Teachings, a legendary treatise on military and political strategy that was supposedly written by — guess who — Jiang Ziya, the first of our illustrious advisers. Of course, this book was almost certainly written by someone else who then attributed it to Jiang Ziya for some extra credibility and marketing power. But the important thing was that this was a must-read book if you wanted to be the kind of adviser who helps found empires. From that point on, Zhang Liang devoted himself to its study.

Nine years passed, and Qin Shi Huang died. His son ascended to the throne, but he inherited a less-than-stable empire, and rebellions rose up all through the land. Zhang Liang himself gathered 100-some people and declared that he was rebelling against the Qin dynasty. Of course, you can’t really do much with 100 people, so Zhang Liang was on his way to join up with one of the larger rebellions when he ran into a group of rebels led by a lowly precinct magistrate named Liu (2) Bang (1).

Zhang Liang and Liu Bang hit it off immediately. Zhang Liang offered up plenty of advice to Liu Bang, and Liu Bang often heeded this advice. So if you were Zhang Liang, here wa a guy who respected you and did what you told him to do, so why go anywhere else? Zhang Liang threw in his lot with Liu Bang, who, as it turned out, would become known as the Supreme Ancestor and found the Han (4) Dynasty.

I can go into immense details here about all the things that Zhang Liang did for Liu Bang, but this supplemental episode is already approaching full-episode length, so I’ll just summarize. Zhang Liang’s strategies proved to be instrumental in first helping Liu Bang play a key role in toppling the Qin dynasty, then in saving Liu Bang’s hide when he was threatened by Xiang (4) Yu (3), the strongest of the rebel leaders, who began vying against each other once the Qin was out of the way. Zhang Liang then provided crucial advice to help Liu Bang begin the campaign that eventually defeated Xiang Yu and made Liu Bang the undisputed ruler of the land.

Unlike some of his colleagues, Zhang Liang was smart enough to know when to walk away. After the Han was founded, he began to stay home more and more on the excuse of being sick, gradually removing himself from the presence of Liu Bang, now ruler of the empire. Liu Bang tried to reward Zhang Liang for his contributions by giving him a huge fiefdom, but Zhang Liang declined, asking only for the county where he and Liu Bang first met. Eventually, Zhang Liang turned into a recluse, leaving the outside world behind altogether to pursue the Daoist path. After he died of natural causes in in 186 B.C., he was posthumously named a marquis. This was a far better fate than what befell some of Liu Bang’s other top officials, as Liu Bang was the distrustful sort who, upon securing power, began to suspect, purge, and execute the people who helped him get that power.

So that covers the four legendary advisers to whom Zhuge Liang is compared in the novel. I hope this gives you a better idea of how high a praise such comparisons are, and a better understanding of some key figures in Chinese history. I’ll see you next time on the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. Thanks for listening.

So THIS was the surprise you were talking about a few episodes ago. The episode was great, since he introduced us to such great advisers in the history of china, these guys certainly single-handely changed the fate of their masters and his empires, i wonder why none of those guys became emperor, since they were so capable of handling the matters of the state, what could they have acomplished if they were emperors…I listened to the episode in the christmas day, so thank YOU for this present John, and of course, merry christmas to you and your entire family 🙂

Thanks Pétrus! Happy holidays to you as well. As to your point about why none of these guys became emperor given their capabilities, many emperors/rulers who founded dynasties/kingdoms were not the best fighters or most cunning strategists, but rather people who had some blend of charisma and ability to make the most out of the warriors and the advisers.

Zhang Liang knew when he was overextending himself. Very Taoist.

Is there any good English translations for the historical Three kingdom era?