Supplemental Episode 012: Liu Bei, Fact and Fiction

We delve into the life and career of the real Liu Bei to see if he is really as virtuous as the novel made him out to be (spoiler alert: No one can be as virtuous as the novel made Liu Bei out to be).

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: More Options

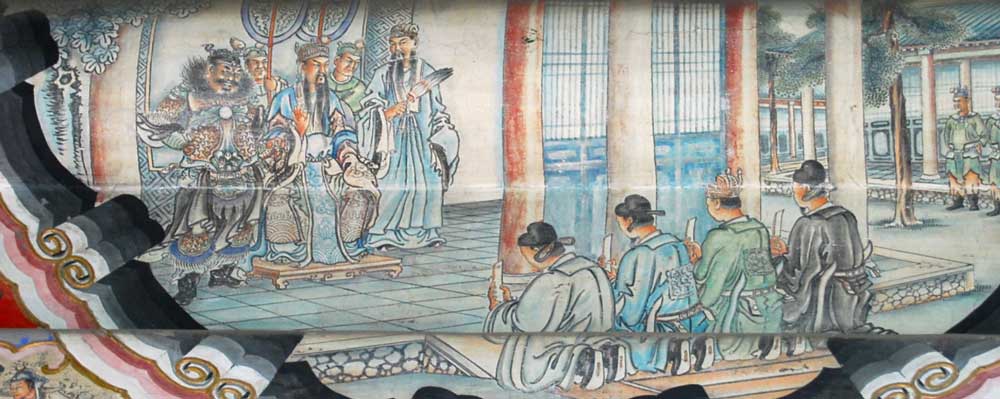

Painting at the Summer Palace of Liu Bei declaring himself king. (Source: Wikipedia)

Transcript

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is a supplemental episode.

Alright, so this is another big one, as we bid farewell to the novel’s main protagonist, Liu Bei. In the novel, he is portrayed as the ideal Confucian ruler, extolled for his virtue, compassion, kindness, and honor, as well as his eagerness for seeking out men of talent. How much of that is actually true? Well, we’ll see. But bear in mind that even the source material we have about Liu Bei should be considered heavily biased, since the main historical source we have, the Records of the Three Kingdoms, was written by a guy who had served in the court of the kingdom that Liu Bei founded, which no doubt colored his view of the man.

Given Liu Bei’s eventual status as the emperor of a kingdom, there were, unsurprisingly, very extensive records about his life and career, and what’s laid out in the novel In terms of the whens, wheres, and whats of Liu Bei’s life pretty much corresponds with real-life events. Because of that, I’m not going to do a straight rehash of his life since that alone would take two full episodes. Seriously, I had to rewrite this episode three times to make it a manageable length, which is why it’s being released a month later than I anticipated. So instead, I’m going to pick and choose from the notable stories about Liu Bei from the novel and talk about which ones were real and which ones were pure fiction. And then I’m going to conclude by taking a look into the novel’s general portrayal of the man compared to his real-life self.

Let’s start with his roots. According to the historical records, Liu Bei was indeed a descendant of an emperor, specifically, the sixth emperor of the Western Han Dynasty. That emperor, it should be noted, died about 300 years before Liu Bei was born. So in the novel, when you hear people tracing Liu Bei’s lineage back to an emperor, just remember that Liu Bei was so many steps removed from the main imperial line that the sitting emperor probably would ignore his request to connect on LinkedIn. There is also some disagreement about exactly WHICH imperial line Liu Bei belonged to, but in any case, by Liu Bei’s time, his twig on the family tree was looking pretty sorry. Just like in the novel, Liu Bei’s family was broke and he was indeed a maker and peddler of straw-woven shoes and mats. This background, of course, gave his future enemies something to hold over his head whenever they needed a good insult on the battlefield.

By the way, in the city of Chengdu, the capital of Liu Bei’s kingdom, he is apparently worshipped as the patron saint of shoemakers. I know, that sounds just like the line from the movie Spinal Tap about there being a real Saint Hubbins who was the patron saint of quality footwear, but it’s apparently at least somewhat true. I found an article from 2005 that described a giant ceremony in Chengdu to offer sacrifices to Liu Bei as, quote, the god of shoes. Now, how much of that was real worship and how much was just an attempt to make a quick buck off Liu Bei’s name? Your guess is as good as mine, though this being China, it’s not like the two have to mutually exclusive.

Next, early in the novel, we were told that as a kid, Liu Bei used to play under a big mulberry tree and that he once said, “When I’m emperor, my canopy will be this big.” That anecdote actually came from the Records of the Three Kingdoms, but honestly, I’m highly skeptical about its veracity, because this just SOUNDS so much like the kind of too-good-to-be-true foreshadowing that one would be tempted to plant in one’s own biography AFTER rising to power so as to build up a tale of preordained legitimacy. We’re told that an uncle heard this and was impressed by Liu Bei. According to the historical texts, this uncle apparently also told Liu Bei to shut up, because, hey guess what? Declaring you’re going to be emperor one day could be considered high treason and grounds for having your entire family exterminated.

The next major part of Liu Bei’s origin story — how he started to make his name — is also true. He did indeed mobilize a local militia with Guan Yu and Zhang Fei to put down Yellow Turban rebels in their region. But as we have already discussed in the supplemental episodes on Guan Yu and Zhang Fei, there is no historical evidence of any oath of brotherhood in a peach orchard.

Liu Bei’s work suppressing the rebellion earned him a modest government post in a small town, but that stint ended when a government inspector came calling and mistakes were made. In the original, more barebones version of the Records of the Three Kingdoms, we’re only told that this inspector came through Liu Bei’s little town on official business, Liu Bei wanted to see him but was denied an audience. This angered Liu Bei, so he stormed in, tied up the inspector, and gave him a hundred lashes.

In the later, beefier version of the Records of the Three Kingdoms, a second source is cited to fill in some details. We’re told that at this time, an imperial decree had been issued saying that anyone who received a government position because of their merits in war were to be dismissed. So Liu Bei figured that this inspector was there to send him packing. When he found out the inspector was staying at the government guesthouse, he went to request an audience, but the inspector declined a meeting, saying he was sick. Well, Liu Bei did not take kindly to this, so he stormed in and declared, “The magistrate has given me secret orders to arrest the inspector.” And with that he dragged the inspector outside, tied him to a tree, and gave him 100 lashes. He even wanted to kill the inspector, but relented when the man begged for mercy.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. Wait a minute, that’s not the way it happened in the novel. As the story in the novel went, this inspector was looking for a bribe and that caused, not Liu Bei, but Zhang Fei to go ballistic and dish out some hardcore justice. But if the Records of the Three Kingdoms is correct, then 1) it was Liu Bei, not Zhang Fei, who did the whipping, and 2) it sounds like the inspector didn’t even ask for a bribe because he didn’t even meet with Liu Bei.

So the historical description of this episode does not exactly reflect well on Liu Bei. I mean, yeah it sucks to get laid off, but taking it out on the mid-level civil servant who was just doing his job and carrying out policy handed down from on high is rather unbecoming of a future emperor and a supposed pillar of virtue. Oh well, nothing a little after-the-fact whitewashing can’t take care of. That inspector was crooked, right? No? Well, he is now. And are you sure you were the one who whipped him? Maybe your recollection of the incident is fuzzy. Are you sure it wasn’t your officer Zhang Fei? Yeah, that’s what I thought. And oh by the way, Zhang Fei is your brother now. Trust me. Just go with it. It’ll play better in the press.

So after saying, “You didn’t fire me; I quit!”, Liu Bei resigned and fled, because oh yeah, beating the crap out of a government official was, you know, illegal. But he didn’t stay in the wilderness too long. A little while later, he got another government job after a good showing in battle against rebels. Unrelated to this, there’s a good story from around this time. Liu Bei was sent to join the battle against a rebel army led by a renegade governor, but on his way, he and his troops found themselves surrounded by rebel forces and the fight was going badly. Seeing things hit the fan, Liu Bei decided, the heck with this, I need to just save my own hide. So he bravely laid down and played possum. Yup, the hero of our novel pretended to be dead. Once the enemy was done massacring his soldiers and left, Liu Bei stole a peek to make sure no one was around, and then he got up and got the heck out of there. Along the way, he ran into an old acquaintance who was riding in a carriage, and this guy gave Liu Bei a lift back to safety. So, not exactly the most glorious chapter in the career of the man who would go on to rule his own kingdom, and you can see why Liu Bei would not be particularly eager to mention this, and why the author of the novel, who was determined to make Liu Bei the virtuous, honorable hero, would just “forget” to include this part.

Anyway, moving on to around the year 190. We had the coalition of warlords against the ruthless prime minister Dong Zhuo, and Liu Bei was part of this coalition. But from the records, it sounds like he was just some anonymous nobody in this campaign. There certainly wasn’t any mention of a mighty battle where Liu Bei and his brothers took on the fearsome warrior Lü Bu. So that particular episode was a total “I need a good action scene” fabrication by the novel’s author.

The decade or so of Liu Bei’s career after the coalition dissolved went more or less like the novel depicted, which meant a lot of ups and downs. There were times when he controlled a city or even a province, but those good times never lasted long before somebody else came along and sent Liu Bei fleeing for his life, and ditching his wives when the going got tough. In fact, he left his wives in the hands of Lü Bu twice and Cao Cao once, and miraculously, he managed to get them back every time.

One famous and apparently true anecdote from this time period was when Liu Bei was serving under Cao Cao in the capital. Liu Bei had made himself part of a conspiracy to assassinate Cao Cao. Not long after that, Cao Cao asked him during a meal which of the great warlords of the time he considered to be true heros. Liu Bei proceeded to rattle off a list of the biggest names of the time, the Yuan Shaos, Yuan Shus, Sun Ces, and so on, only to have Cao Cao dismiss them all and then tell Liu Bei that the only true heroes were Liu Bei and himself, and Liu Bei was so shocked that he dropped his chopsticks.

Anyway, after that eventful decade, by the year 202, Liu Bei was 42 years old and nothing more than a refugee hiding from Cao Cao, holed up in a small city and surviving on the kindness of his distant relative Liu Biao, who was the imperial protector of Jing Province. But then entered Zhuge Liang, and yes, Liu Bei really did make three trips to see him. There is, however, no mention in the historical records about whether Liu Bei was so obsessed that he thought every person he came across was Zhuge Liang.

At their first meeting, in the year 207, Zhuge Liang told Liu Bei that the place to be was, well, right where he already was — Jing Province. It was at this famous meeting that Zhuge Liang laid out his grand vision for Liu Bei — take control of Jing Province, then go west and take Yi Province, and use these two regions as your base. Make nice with the state of Dongwu in the east, and wait for circumstances to turn in your favor before invading the Heartlands from both Jing Province and Yi Province.

Having a grand plan was nice and all, but as we already know, Liu Bei was not quite done being on the lam just yet. Pretty soon, Liu Biao died and Cao Cao came calling for Jing Province, so Liu Bei again took off. Now, in the novel, we have as a demonstration of his honor that he refused to try to take Jing Province from Liu Biao’s younger son even though everyone was advising him to do it. And this part was historically accurate. So instead, they found temporary sanctuary with Liu Biao’s elder son and then reached out to Dongwu to ask for help against Cao Cao. All of that, of course, led to the Battle at Red Cliff, which we have already covered in a previous supplemental episode.

So after Cao Cao’s southern campaign literally went up in flames at Red Cliff, Liu Bei finally got to catch his breath. He used this respite to begin carving out some breathing room for himself. This was when he took four counties in the south of Jing Province and later became de facto imperial protector of JIng Province when Liu Biao’s eldest son died. Now, in the novel, the conquest of this part of Jing Province was an extremely acrimonious affair as both Liu Bei and Sun Quan wanted that area and there were lots of backstabbing going on, but I didn’t find much evidence of that in the historical records. Instead, the records say that after Liu Bei had taken that piece of territory, Sun Quan offered Liu Bei his sister’s hand in marriage to cement their coalition and to officially “lend” him Jing Province. So while I’m sure they were all looking out of for their own self-interests, at least on the surface, they appeared to be on good terms.

Now, I did find some Game of Thrones-style frenemy action where the Riverlands were concerned. In the novel, it was always Liu Bei who had his sights set on this fertile territory to the west. But according to the Records of the Three Kingdoms, Sun Quan also wanted the Riverlands, and he once asked Liu Bei to join him in an expedition to conquer the territory. But Liu Bei missed the lesson about sharing with other children and wanted the Riverlands for himself, so he told Sun Quan, “The Riverlands are still too strong to take, and if you undertake a distant campaign, Cao Cao would surely make a move on your own territory.”

When Sun Quan was still unconvinced and was sending his army westward anyway, Liu Bei made a big to-do about how if Sun Quan insisted on attacking the Riverlands, then he would give up public life and retire into the mountains so that he would not be seen as a dishonorable man by the realm for attacking a territory held by a fellow member of the imperial house. In the novel, that message was delivered by Zhuge Liang to the Dongwu commander Zhou Yu as a way to rub salt in the wound after Zhuge Liang foiled Zhou Yu’s scheme of pretending to help Liu Bei take the Riverlands. But that part of the novel is actually based on history. In real life, Liu Bei’s little act, plus his obvious reluctance to help Sun Quan with the campaign, convinced Sun Quan to call off the whole operation.

So after convincing Sun Quan to stay put, Liu Bei soon began his own Riverlands invasion, and it went down pretty much like it was described in the novel. The ruler of the Riverlands, Liu Zhang, invited Liu Bei in as an ally against outside threats, but in the end found that he had brought about his own demise by allowing Liu Bei into the Riverlands.

In the novel, there were some tense moments between Liu Bei and the state of Dongwu after he conquered the Riverlands. Namely, Dongwu wanted Jing Province back now that Liu Bei had territory of his own, but Liu Bei, surprise surprise, didn’t really want to give it back and so tried time and again to stall and deflect. Well, it turns out that things were actually much more tense in real life than in the novel. In real life, Sun Quan got fed up and decided to send the general Lü Meng to lay siege to three counties in Jing Province that were under Liu Bei’s control, and Liu Bei responded with force as well, garrisoning tens of thousands of troops in key areas to prepare for a battle.

But just as the two sides were about to go at it, Liu Bei got word that Cao Cao had taken the region of Hanzhong, which meant he was in position to invade the Riverlands. So Liu Bei hammered out a peace treaty with Sun Quan, dividing Jing Province with him, and then went back home to face Cao Cao. That started a four-year struggle for the region of Hanzhong, which Liu Bei eventually won. With Hanzhong in hand, Liu Bei declared himself the King of Hanzhong, at the age of 58. And this was really the apex of his career, even though he would declare himself emperor two years later. Not long after he conquered Hanzhong and made himself king, Liu Bei lost Jing Province when his longtime general Guan Yu was captured and killed by Dongwu. That marked the beginning of Liu Bei’s fall.

In the year 221, Cao Cao’s son Cao Pi ended the Han Dynasty and declared himself emperor. That prompted Liu Bei to say, you’re not the real emperor; I’m the real emperor, and reports of the demise of Han Dynasty are greatly exaggerated because the dynasty is doing just fine over here in the Riverlands. But soon after that, Liu Bei decided that his first major act as emperor would be to exact vengeance against Dongwu for the death of Guan Yu and the loss of Jing Province. That campaign, of course, ended badly for Liu Bei. He was crushed by the Dongwu commander Lu (4) Xun (4), forcing him to retreat to the city of Baidi (2,4), where he eventually died in the year 223, at the age of 63.

So those are the broad strokes of Liu Bei the historical figure, but what about Liu Bei the man? In the novel, he was portrayed as the very ideal of a Confucian lord, a virtuous and compassionate ruler who recognized and respected talented men. How accurate is that characterization?

In the Records of the Three Kingdoms, at the end of the chapter on Liu Bei, the author offered this summation:

“The First Emperor was liberal, firm, and generous. He recognized men of talent and treated them with respect. He possessed the air of the Supreme Ancestor, and the talent of a hero. He entrusted his kingdom and his heir to Zhuge Liang, without second-guessing or suspicions. Theirs was a model relationship between lord and vassal. His ability and authority as a ruler could not match that of Emperor Wu (3) of the kingdom of Wei, aka Cao Cao, because his quality was not great. Yet he persevered in the face of adversity and refused to submit to another man. When he sensed that Cao Cao would not be able to tolerate him, instead of rushing to confrontation and competition for the realm, he instead avoided Cao Cao and escaped calamity.”

So there’s a lot packed into that paragraph, and not all of it good. Now the first couple sentences were obviously glowing praise. I mean, the author compared Liu Bei to the guy who founded the Han Dynasty. But remember, the man who wrote the Records of the Three Kingdoms once served in the Shu court, so praise from him is kind of like your mom telling you that you’re really cool.

What’s interesting to me is the sentence about how Liu Bei was not quite the equal of Cao Cao. It seems an odd thing to say right after praising Liu Bei to the hilt. Personally, my guess is that the author of the Records of the Three Kingdoms put it in there to cover his rear. When he was writing this, he was serving in the court of the kingdom formerly known as Wei, which was, of course, the kingdom founded by Cao Cao’s heirs. So maybe he felt the need to not go overboard in praising the lord of a rival kingdom.

Of course, you could also argue another interpretation: That Liu Bei really wasn’t Cao Cao’s equal. After all, Liu Bei did seem to lose a lot more battles than he won, especially before the last decade of his life. Sure he could slap some hapless Yellow Turban rebels around, but when he went up against somebody of note, like a Cao Cao or a Lü Bu, it usually didn’t end well for him. And if you just look at territorial claims, Cao Cao did dwarf Liu Bei in the size of their domains. Among the three kingdoms, Cao Cao controlled the largest portion of the empire, while Liu Bei’s kingdom was the smallest and most remote. Of course, they didn’t exactly start on equal footing either. Cao Cao was connected to a powerful eunuch while Liu Bei was a dirt-poor nobody. Yes, a dirt-poor nobody with imperial blood in his veins, and we did see cases where that imperial connection opened doors for him, but he definitely had longer odds to beat to emerge as one of the three winners in the giant free-for-all that was the last days of the Han empire.

Then there’s that sentence about his relationship with Zhuge Liang. To me, Liu Bei certainly reaped huge PR points from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, which painted him in a very positive light. However, I do think he suffered from the novel making Zhuge Liang out to be the most brilliant man in history. Basically, if you believed the novel, Liu Bei’s greatest accomplishments were finding Zhuge Liang, listening to Zhuge Liang, and entrusting his kingdom to Zhuge Liang when he died. Basically, Zhuge Liang made Liu Bei, as far as the novel was concerned.

Now, let’s give credit where credit is due. Zhuge Liang certainly gave Liu Bei the blueprint for his eventual success, telling him to build his base in Jing Province and the Riverlands. But Zhuge Liang’s role in Liu Bei’s military success has in some cases been greatly exaggerated. In our supplemental episode on the Battle of Red Cliff, for instance, we addressed the point that Zhuge Liang didn’t really seem to play much of a role in that battle, contrary to the novel. There are also other battles that Liu Bei won where we don’t really find any mention of Zhuge Liang’s involvement. But in the novel, many of these victories were credited to Zhuge Liang, which I think takes something away from Liu Bei’s abilities as a commander.

A good example of this is Liu Bei’s decision to attack Dongwu after becoming emperor. In the novel, this was depicted as basically the only time Liu Bei ever rejected Zhuge Liang’s advice, and sure enough, he ran head first into a disastrous defeat that basically ended any hopes he had of reuniting the empire. But in real life, there is no mention of Zhuge Liang having advised against the campaign. We do have records of Zhao Yun and others speaking up against attacking Dongwu, but nothing about Zhuge Liang doing so. And remember, he was the prime minister, so if he had spoken out against an attack, I think we probably would have had some mention of that in the historical records.

During the 100th episode Q&A session, I talked about how the author of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms likely identified with Zhuge Liang as someone longing to find a worthy lord who recognized his talent. That is perhaps why Liu Bei was portrayed as the Confucian ideal for a ruler in the novel. Note that the Confucian ideal for a ruler wasn’t someone who could claim to be the mightiest warrior or the smartest strategist. Instead, it’s someone who recognized talent and allowed talented men to do their thing. That, I think, is the reason for the way the Liu Bei-Zhuge Liang relationship is depicted in the novel. Liu Bei achieved greatness not because he was the strongest or smartest, but because he respected and empowered great talents like Zhuge Liang, and THAT, perhaps, was the moral of the novel.

Now, what about Liu Bei’s character? His name is often invoked as a model of two qualities: ren (2) yi (4). The first quality, ren (2), can be translated as humane or compassionate. The second quality, yi (4), is translated as honorable. So was he really the model of compassion and honor?

Undoubtedly, there is a high degree of hyperbole and propaganda at play here, but we do see some evidence to back up the compassionate part of that characterization. For instance, a story from the Records of the Three Kingdoms tells us that when Liu Bei was in charge of a county early in his career, there was a local man who had always looked down upon this former weaver of straw mats and sandals and detested having to live under his administration. So this guy hired an assassin to kill Liu Bei. As the story goes, the assassin showed up at Liu Bei’s residence, and Liu Bei, ignorant of the guy’s true intentions, treated this total stranger with kindness and respect. The assassin was so touched by this that he couldn’t bring himself to do the job. Instead, he told Liu Bei the truth and then took his leave.

Another story from the historical records also speaks to Liu Bei’s compassion, and this is one that’s also in the novel. While he was on the run from Cao Cao in Jing Province, Liu Bei was traveling with tens of thousands of civilians who decided to throw in their lot with him and follow him wherever he might take them. This unwieldy entourage forced him to travel at a snail’s pace, and some of his advisers were telling him to ditch the throngs and hurry on ahead to safety. But Liu Bei refused. According to the Records of the Three Kingdoms, he said, “To accomplish a grand enterprise, you must make the people your foundation. Right now, the people have pledged themselves to me, so how can I bear to abandon them?” And so he kept trudging on, which of course, allowed Cao Cao’s troops to catch up, forcing him to flee without his wives. So note: Never abandon the strangers who have pledged themselves to you, but your wives? That’s a different story.

Now, as for the honor part of Liu Bei’s characterization, we see a more ambiguous picture. Yes there are instances from the historical records of him acting honorably. For instance, when Zhuge Liang advised him to take Jing Province from Liu Biao’s heirs, the real-life Liu Bei really did say that he couldn’t bear to do it. But on the other hand, we do see a lot of things that would qualify as less than honorable. Like the aforementioned instance where Liu Bei dissuaded Sun Quan from launching a campaign to conquer the Riverlands because he wanted the Riverlands for himself. And there’s the time when Lü Bu, upon being captured by Cao Cao, begged Liu Bei to put in a good word for him and Liu Bei just nodded.

And then he did the exact opposite thing and convinced Cao Cao to execute Lü Bu. Oh, and there’s the fact that Liu Bei just seemed to have a tendency for gobbling up the territory of people who take him in. First it was Tao (2) Qian (1), the imperial protector of Xu Province who asked Liu Bei to come help fend off Cao Cao. Then, it was Liu Biao, who gave him shelter in Jing Province. And of course, there was Liu Zhang, who brought him into the Riverlands to, ironically, help fend off outside threats.

Now, in some of those cases, there were extenuating circumstances. Tao Qian and Liu Biao both died, leaving their territories in need of a leader. But still, there is no denying that both in the historical records and in the novel, Liu Bei comes off as more of an opportunist than a man of unshakable honor. In fact, you can see the novel kind of struggling to reconcile the man’s track record with its attempt to portray him as the model enlightened lord. In the novel, when you see Liu Bei doing something that’s not quite on the level, he is often portrayed as being conflicted. He doesn’t want to take the necessary course of action because he thinks it’s dishonorable, and yet, in just about every case, he had some VERY persuasive and insistent subordinates who drag him along kicking and screaming. So in the end, as much as he protests, he ends up doing the necessary thing that he thinks is dishonorable. “Oh I don’t want to be the imperial protector of Xu Province, but ok you twisted my arm. Oh I can’t possibly bring myself to take JIng Province since it belonged to my kinsman, but alright since you guys insist. Oh I would never take the Riverlands from you, my dear brother Liu Zhang, but you see, my guys all insisted, and you know how persuasive they can be. It’s not like I’m their lord or anything. Oh wait, I guess I am, but I really feel bad about this, and I think that’s what really matters, right?”

One other aspect of Liu Bei’s character that I want to address is his political ideology. In the novel, he is portrayed as the ultimate Confucian liege. But in actuality, this portrayal required a dramatic exaggeration of his Confucian tendencies. The real Liu Bei could perhaps be best described as a legalist in Confucian clothing. Now, remember that Cao Cao was more of a straight-up legalist, and the novel portrays Liu Bei as his Confucian nemesis, but really it sounds like the differences in their political ideology were not so black and white. And I should point out that Liu Bei was hardly alone in this regard. In fact, legalism with Confucian characteristics had been the dominant governing ideology for most of the Han dynasty. The Qin dynasty, the predecessor to the Han, had gone with a pure legalist approach, and it was so harsh that the rulers, officials, and scholars of the Han believed it was the reason the Qin collapsed so quickly. So while keeping an emphasis on the rule of law, the Han also tempered it with moral considerations from the Confucian school of thought.

If you look closely, you can see some of Liu Bei’s legalist side come through in the novel. After taking over the Riverlands, he and Zhuge Liang replaced the existing laws of the region with a very strict system of rewards and punishments. In the novel, when one of the Riverlands officials expressed concern that this might not win them points with the people in the region they had just conquered, Zhuge Liang explained that the previous administration had lost control of the region precisely because of its lax laws. Zhuge Liang pointed out that the deposed ruler had tried to use small acts of benevolence or generosity to curry favor with a few individuals, but he never earned their loyalty because they took his kindness for granted. What was needed, Zhuge Liang argued, was a strict, clear set of laws that made sure everyone knew their place and their responsibilities. This scene has its basis in history, as the real Liu Bei apparently was not a fan of the lax ruling style of Liu Zhang, the man who lost the Riverlands to Liu Bei. So Liu Bei gave Zhuge Liang the leeway and support to implement a much stronger set of laws.

Alright, I think that just about wraps it up for Liu Bei. My assessment of him is that he probably didn’t get as much credit in the novel as he should have for his abilities, but that is offset by the ridiculous amount of propaganda about what an all-around wonderful guy he was. He certainly did have his compassionate and honorable moments, but I think in reality, he was probably as opportunistic as anyone from this era who wanted to be somebody, and he did manage to become somebody. Considering his lowly origins, that was as great an accomplishment as any from the Three Kingdoms period. I hope you enjoyed this supplemental episode, and I’ll see you next time on the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. Thanks for listening!

This was really insightful and well written. I have followed the novel as gospel, so it is refreshing to see the truths mixed into the comparison! Thanks and I can’t wait to read more.